Few things get games journalists more riled up than a colleague who refuses to toe the line. This time, it’s veteran video game journalist Dean Takahashi who has come under fire for … doing his job?

Because he naively reported the truth, Takahashi remains in the crosshairs, and his peers and colleagues have taken to social media to lambast him for his reporting.

Takahashi’s crime was to investigate the long-standing allegations of “toxic work culture” at French game development studio, Quantic Dream, best known for developing the PlayStation games Beyond: Two Souls, Heavy Rain, and Detroit: Become Human. According to Takahashi, the charges against Quantic Dream were largely specious.

In 2018, right before the release of Detroit, an employee resigned amidst a scandal alleging a hostile work environment. During the investigation, led by three prominent French outlets, the employee alleged that the studio leads David Cage and Gillaume de Fondaumiere participated in or encouraged sexism and racism around the office. There were further allegations of violations of French labor laws. Allegedly, the studio management enforced a “crunch time” schedule prior to their games’ releases, forcing employees to work for an additional 15 to 35 hours per week for twelve months prior to Detroit’s release. The company’s HR department was said to have terminated contracts of anyone unhappy with the arrangement.

A French labor court cleared Quantic Dream of the most serious allegations against it, but the damage to their reputation remains. This is likely why Takahashi decided to subject the narrative to scrutiny. The line is clear, however: games journalists whose writing at all undermines the union-politics of their left of left colleagues are to be cancelled.

Because he naively reported the truth, Takahashi remains in the crosshairs, and his peers and colleagues have taken to social media to lambast him for his reporting.

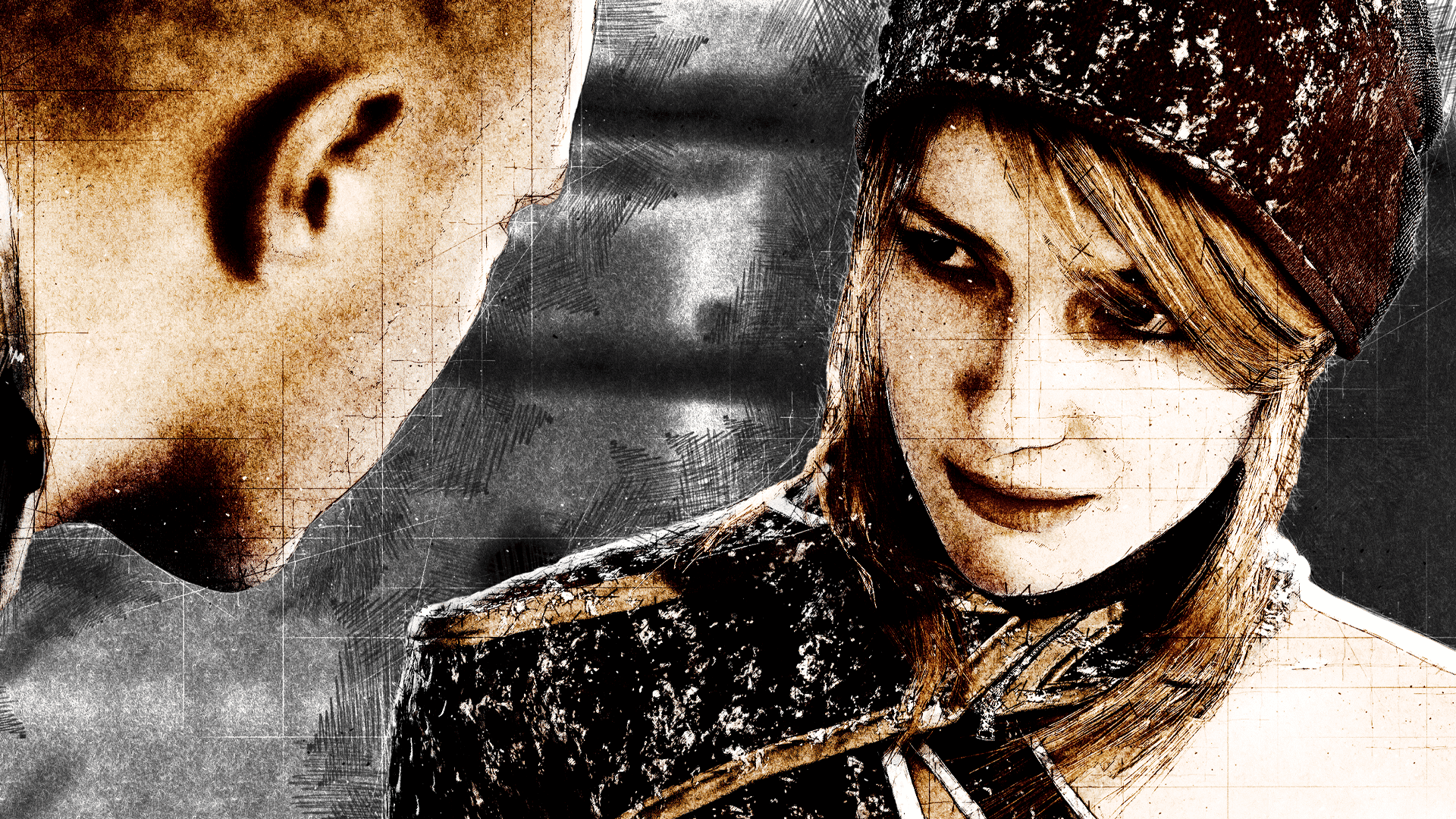

[caption id="attachment_181756" align="alignnone" width="1920"] Bryan Dechart and Clancy Brown (Detroit: Become Human, 2018)[/caption]

Bryan Dechart and Clancy Brown (Detroit: Become Human, 2018)[/caption]

REPORTING BY DEAN TAKAHASHI REVEALS QUANTIC DREAM WAS THE ACTUAL VICTIM

In 2018, Quantic Dream released an official statement in response to the allegations, arguing that there was a “veritable smear campaign.” David Cage responded directly to the reports in Le Monde to rebut accusations of bigotry. “You want to talk about homophobia? I work with Ellen Page, who fights for LGBT rights. You want to talk about racism? I work with Jesse Williams, who fights for civil rights in the USA. Judge me by my work,” he said. Though having a gay friend and a black friend isn’t the best defense, but I get the point; Cage argues that the people he works with, the games he puts out, and the content they revolve around goes against claims of misogyny and racism. His actions spoke louder than the accusations against him.

“You want to talk about homophobia? I work with Ellen Page, who fights for LGBT rights. You want to talk about racism? I work with Jesse Williams, who fights for civil rights in the USA. Judge me by my work.”

Two years later, Dean Takahashi, a journalist for VentureBeat, followed that thread and spoke to several current employees of the company in his piece on “How Quantic Dream defended itself against allegations of a ‘toxic culture.’”

Reporting from the company’s perspective, Takahashi spoke to 16 current employees of Quantic Dream and conducted interviews with both Cage and de Fondaumiere. His article goes into detail about the single allegation that sparked two years of sensationalist coverage in the French press and the international games media. Takahashi interviewed over a dozen Quantic Dream employees, including the studio heads, who detailed their shock and dismay at the French media’s “sensationalist” coverage of the controversy.

According to the employees, the trouble started when one of the studio’s programmers made photomontages of his coworkers by photoshopping them onto pictures of celebrities and historical figures in a humorous fashion. While most of them didn’t mind it, an IT manager, who later resigned, took issue with it and raised a formal complaint, prompting management to order the programmer to stop.

The IT manager allegedly accepted the apology, and that was to be the end of it—until he demanded that the programmer be fired. According to the studio, the employee threatened to run to the press unless they paid him a year’s worth of salary plus an additional 40 percent for hurt feelings. Cage, who refers to it as blackmail, rejected the demand, and the disgruntled employee made good on his ultimatum, which led to the resulting coverage in the French press and international games media.

Multiple authorities, including one American and two French audit companies, cleared the studio of any wrongdoing with regards to its labor practices. The French government body, URSSAF, also investigated the allegations made by the French press and reported that the company was indeed above board.

They called the stories “bullshit.” One of the employees recalled in horror the experience of having his teenage children asked him about what it was like to work in such a hostile environment.

Takahashi interviewed the French reporters responsible for the articles, who argued that Quantic Dream was not exactly forthcoming in its responses to the press and behaved with hostility. One journalist called the company’s responses “awkward PR spin,” and shared his condolences to the employees who “still suffer from what they described as a toxic workplace.”

Current employees of Quantic Dream disagree with the media’s assessment of the company. Speaking in a group setting with Takahashi, they explained that they were surprised, shocked, and indignant about the way their studio was being portrayed in the media. They called the stories “bullshit.” One of the employees recalled in horror the experience of having his teenage children asked him about what it was like to work in such a hostile environment.

The employees hit back against allegations that the company didn’t compensate them for crunch time, stating that Quantic Dream was open about its policies. They expressed that the news coverage depressed and confused them because none of them could think of any situation where they felt they were working in a toxic environment.

Despite the trials and tribulations, Cage says that Quantic Dream is in no great danger of faltering. The studio as a whole has stayed together to make more games. It’s worth noting that Detroit was also financially successful.

[caption id="attachment_181755" align="alignnone" width="1920"] Jesse Williams as Markus. (Detroit: Become Human, 2018)[/caption]

Jesse Williams as Markus. (Detroit: Become Human, 2018)[/caption]

UNIONIZING AWAY INDEPENDENT CREATORS AND CREATIVITY

Beneath the surface of the Quantic Dream/Takahashi controversy is an important on-going debate in the video game community: games unions.

As the video game industry has grown in recent years, surpassing both the film and music industries combined, calls for video game developers to unionize have been rampant. Long hours, limited-term contracts, and high employee turnover have all become hotly debated topics.

To outsiders and those new to the game industry, being a game developer can seem more like a nightmare than a dream job.

To outsiders and those new to the game industry, being a game developer can seem more like a nightmare than a dream job. Even luminaries like Rockstar Games co-founder Dan Houser talked about how the company’s leads “were working 100-hour weeks” to release the studio’s biggest game to date, Red Dead Redemption 2.

This quotation was taken out of context by the gaming press to imply that the vast majority of the studio’s employees suffered in order to release the game. But to those in the industry, Houser’s remarks conveyed his passion for the project—which is evident in the quality of the finished product. Therein lies the difference between pro-unionists and the gaming community: one is concerned only with who makes the video games and, the latter does not want to see creativity tampered with.

While efforts to unionize may seem well-intentioned, especially when pushing back against unreasonable demands for long hours, organizations like Game Workers Unite have placed a strong focus on “having a real guarantee that worker voices are engaged in the direction of these companies.” In other words, these unionists would like to turn the studios they work for into collectives, defying any sort of creative direction, concentrating the power to blacklist anyone from the workforce if they fall out of line.

That’s not to say there aren’t things that can be improved about the game industry—like the kinds of complaints that, however baseless, initially surfaced about Quantic Dream. But these are all issues that can be solved with adequate training, management, and Human Resources. You don’t need unions to get people to stop acting like jerks in the office.

Furthermore, unions wouldn’t help flagging companies from going under—they’d accelerate the decline of smaller studios incapable of meeting its milestones in addition to having to pay its employees at whatever set rate the unions come up with. A core feature of working in the video game industry is that you don’t really need technical qualifications to be good at your job. The industry’s best-known creators, including John Carmack, and Todd Howard, the creators of Doom and Skyrim, respectively, were all self-taught. Minecraft, arguably the world’s most profitable game, was made by a lone hobbyist before he hired a team and sold the game to Microsoft for 2.5 billion dollars.

If unions were to concentrate power and dominance of the video game market—the same way the Screenwriters Guild of America or SAG-AFTRA does—independently made games or those that refuse to hire union workers would struggle more than they already do and would be unable to compete with the big boys when hiring talent.

[caption id="attachment_181754" align="alignnone" width="1920"] (Detroit: Become Human, 2018)[/caption]

(Detroit: Become Human, 2018)[/caption]

IN RESPONSE, GAME UNION ACTIVISTS ATTEMPT A CANCEL CAMPAIGN AGAINST TAKAHASHI

Despite Quantic Dream’s studio’s redemption arc, the company remains censured by fake news media, with international game journalists now leading a baseless charge against Cage, as well as anyone who defends him. Now, Takahashi is the primary target of a contingent of high profile game journalists who are accusing him of journalistic impropriety.

What’s implied here? That it’s acceptable for games journalists to lie about a company and its employees as long as it serves some greater purpose—in this case, a pro-union agenda.

Posting on Twitter, Kotaku news editor Jason Schreier expressed solidarity with the French journalists, who, in his estimation, “have to deal with this BS.” He argues that anyone who reports on so-called “toxic conditions” is dealing with a hard enough situation and that the industry does not need what he calls “corporate-friendly journalists trying to discredit that hard work.”

“Video game journalism has taken some great strides over the past few years, but there are still those who value access over truth. Which, fine, to each their own. But to use that access to obfuscate truth to protect powerful people is an embarrassment to the profession,” Schreier says. Schreier went on to call Takahashi’s attempts to discredit the work of the sensationalist French press “one of the most pathetic things I’ve ever seen in the games press.”

Kotaku reporter Cecilia D’Anastasio was more charitable in her take, stating that she is “open to scrutinizing media narratives,” but that the way the interviews were set up makes her raise questions. “A lot of people doing accountability reporting in games will tell you that, most of the time, their reporting exists in spite of game companies' efforts and not because of them,” she says.

Schreier was joined by Lucy O’Brian, a constant gnat in my mentions tab, who described the article as PR spin. “If PR arranges a series of interviews to aid you in an effort to debunk genuine investigative reporting, you’re not a journalist, you’re a mouthpiece,” she said. Schreier and his cadre of journalists are active proponents of leftist labor unions in the game industry, and frequently promote not just your typical calls for fair wages and fair hours, but also an explicit social justice agenda.

What’s implied here? That it’s acceptable for games journalists to lie about a company and its employees as long as it serves some greater purpose—in this case, a pro-union agenda.

Vive la révolution.

It’s about ethics in game developer unionization.

It’s about ethics in game developer unionization.