American conservatives are always on the lookout for a ???silver bullet??????a legal process that can shortcut political gridlock and restore the constitutional system of government we hold dear. Whether it is hoping for an Article V convention, a lawsuit to stop nonenforcement of the laws, a Senate parliamentary trick, or renewed judicial scrutiny of laws, we always hope to avoid the hard work of politics.

Once in a while, however, an idea comes around that promises not immediate political salvation, but a renewed discussion about first political principles. Saving Congress from Itself is one such book, and its thesis???that Congress should eliminate grants-in-aid to the states???is provocative.

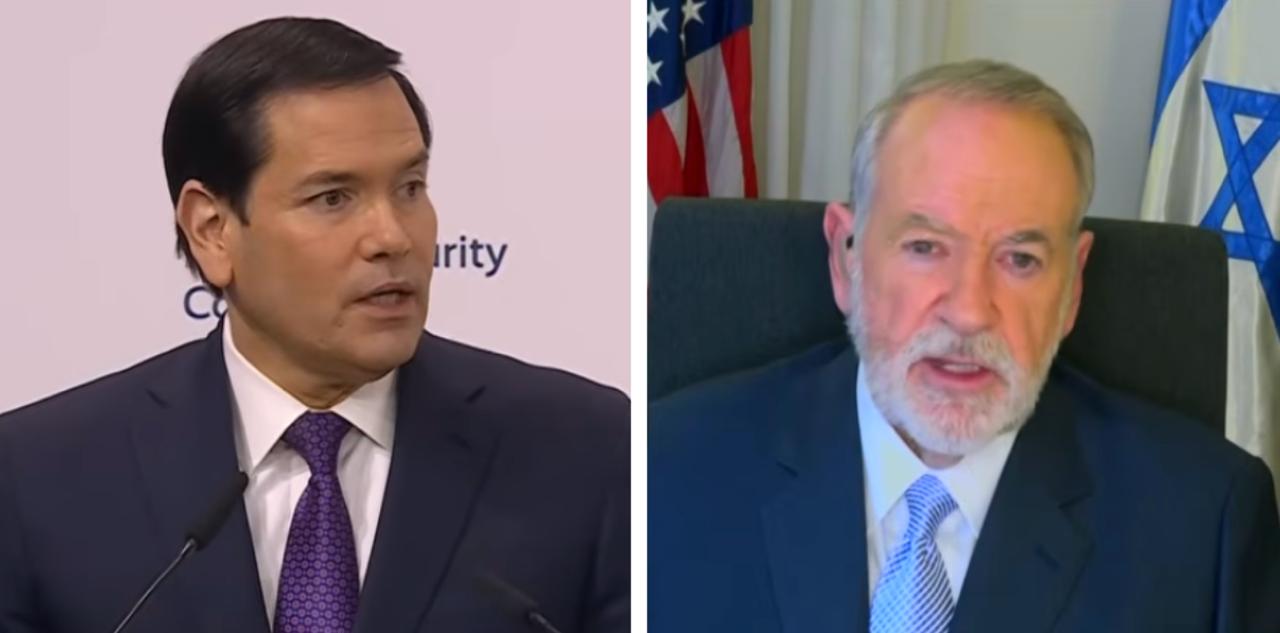

The author of the book is James L. Buckley. As one of my colleagues at the Heritage Foundation notes: ???the other Buckley.??? But the former United States Senator from New York (the only Conservative Party candidate to ever win statewide office) and former Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, James Buckley should in nowise be considered less influential than his more well-known younger brother, William Frank. James Buckley has had an outsized impact on American politics, not only as an undersecretary of State in the Reagan administration, but also as lead plaintiff in the most influential case in modern election law???Buckley v. Valeo.

His new book provides startling details about how and why the federal government runs roughshod over the states. Our constitutional system ensures that the federal government is one of limited and defined powers. The federal government cannot, for example, set up a national system of public schools, because no such authority is outlined in Article 1, section 8 of the Constitution. But ever since the 1937 Supreme Court case of Steward Machine Co. v. David, and reinforced by subsequent cases such as South Dakota v. Dole, it is clear that Congress has found a constitutional workaround. That workaround is the Spending Clause. Rather than set up a national school system, for example, Congress can instead give federal money to the states to pay for education, and Congress can attach extremely onerous requirements to that federal money. The siren song of filthy lucre is often too much for the states, and what Congress cannot regulate directly, it now does indirectly.

How big is the problem? Buckley gives some startling numbers, and some darkly humorous examples. In 2010, over $600 billion was spent on federal grants-in-aid. This money, Buckley contends, creates opportunities for waste: there are more than 100 programs dealing with surface transportation, 82 dealing with teacher training, 47 job training programs, and on and on.

Grants-in-aid to states also have political costs. They stifle state policy innovation by chaining states to federal priorities; they encourage wasteful projects that states and locales might not otherwise pursue, driving a wedge between state electorates and state officials, and they entrench a lobbying class that distributes this manna from heaven. It is this last point that Buckley, as a former Senator, is uniquely qualified to critique. ???Once upon a time,??? Buckley laments, ???the United States Senate was known as ??? the world???s greatest deliberative body???.??? Now, Senators spend much of their time channeling the river of federal money to constituents, and spend less of their time deliberating about policy. Grants-in-aid are partly responsible for the ???mile-wide and inch-deep??? knowledge of federal politicians. (Not to mention constant electioneering, a problem that leads Buckley to suggest term limits as an ???ancillary??? reform). You can hardly blame politicians for being rationally self-interested actors???those politicians who don???t spend all their time seeking donations and distributing pork (including securing federal grants) to constituents are at a competitive disadvantage to other candidates who are willing to do so.

What is to be done? In Buckley???s mind, Congress must eliminate grants-in-aid. It can perhaps wind them down so that states may more smoothly fill in the accounting and administration gaps. Such a reform flies in the face of how Washington works today, but Buckley has faith in the American electorate.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Buckley???s proposal is that it appears politically neutral. Certainly, there are many grants-in-aid that conservatives oppose. But federalism is not something that benefits the right over the left, or the left over the right. There is a real opportunity here for mutual arms reduction by devolving power to the states. But this does not mean that Buckley???s proposal is a silver bullet. Moreover, many interlocking interest groups will need to be brought on board to give the idea a real chance of succeeding.

As the 2016 Presidential election advances, now, more than ever, we need a recommitment to conservative principles and a slate of ideas that can improve our country. Hopefully some candidate or group of candidates will pick up Buckley???s ???modest proposal??? as a part of a broader devolutionary platform that both ???emancipates the states and empowers their people.??? It is this kind of return to localism that can reenergize our Republic.